The Jersey Journal, a local newspaper that seldom did its best to cover my hometown in Hudson County, shuttered this weekend when its big sister, the Star-Ledger shut down its presses.

I started writing for the Jersey Journal in 2010. The paper provided me with my first paying job in journalism, my first chance to see my work in print and on The Colbert Report, attend my first New York Fashion Week, my first press trip–to Atlantic City, gave me my first cover story, and the chance to cover every Yo La Tengo Hanukah residency at Maxwell’s in Hoboken.

It all started after I graduated journalism school wrote a letter to the editor complaining how one of their reporters had plagiarized a story from my blog. I suggested they hire me instead of stealing my work, and in response, they offered me $35 a story, or $50 with photos.

I decided I could be insulted or I could build a career. And learn photography.

At the time, I had wanted to break into food writing after working at a fancy restaurant downtown. I had finally broken through a few months earlier when I created one of the first parody accounts on Twitter.

Media circles had been complaining about the new restaurant critic at the New York Daily News–the first non-anonymous critic at a national newspaper. A glossy headshot accompanied each of Danyelle Freeman’s reviews, a word soup of sentence fragments, the Times later described as “the top-of-the-head immediacy of a blog with the breezy tone of a late-night phone call from a friend on her way home from a night of sangria and tacos.“ Or maybe they were describing me, I can’t remember.

Freeman was an early influencer whose only interest was in self-promotion, and while no one liked what her hiring meant for the future of journalism, no one was motivated to do anything about it either. (At least before 2015, when the socialite ex of Freeman’s husband threatened to skin her alive for stealing her man.)

So I joined Twitter using her RestaurantGirl pseudonym ahead of that February’s South Beach Wine & Food Festival. At home in New York I live-tweeted the weekend in her voice.

One example: Everyone is off judging Hamburglars.

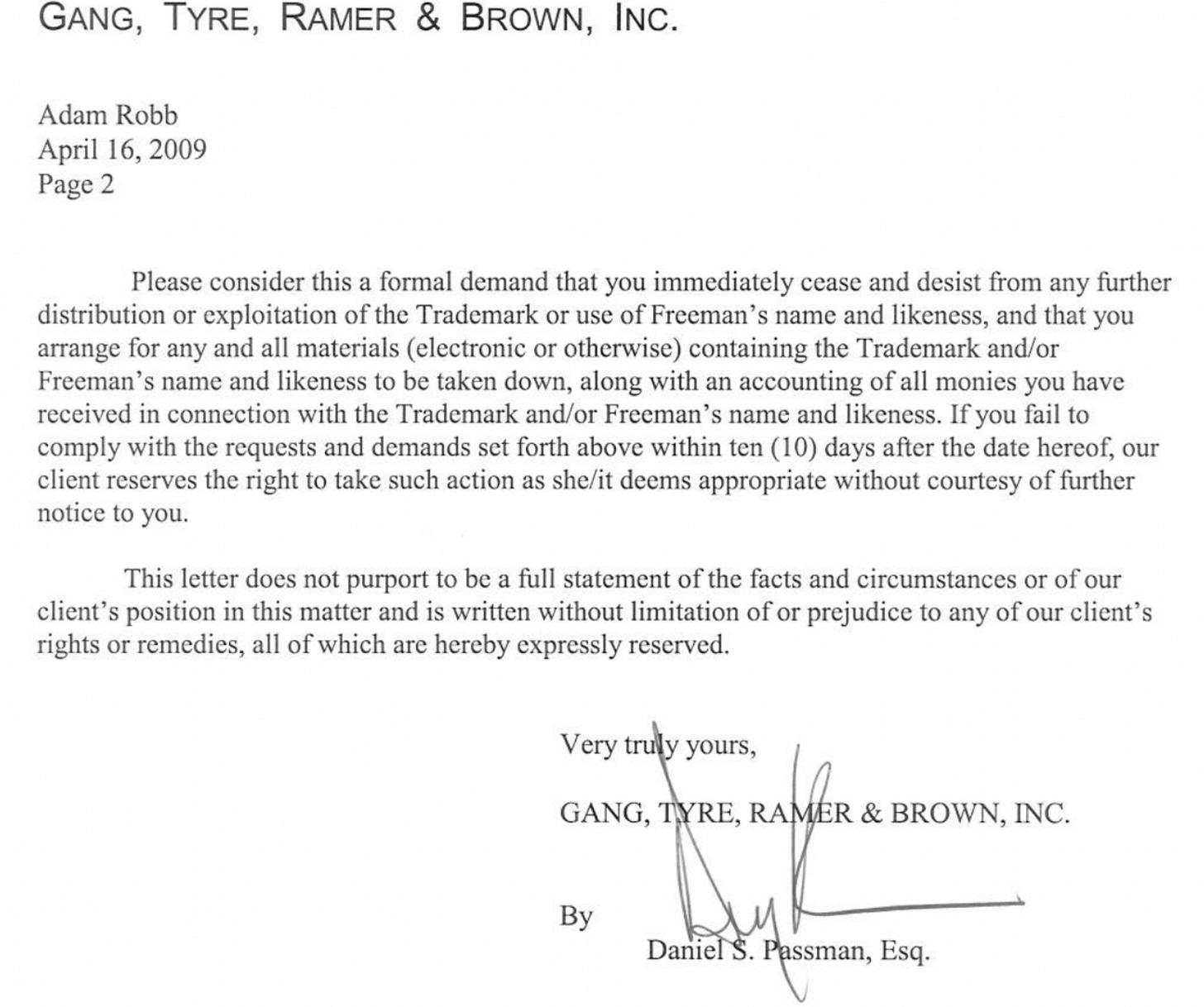

This was highly controversial at the time! When she finally realized I wasn’t her, she lawyered up ,and sent me a cease and desist letter. Her lawyer threatened to sue. And not just any lawyer.

This is the same powerhouse firm that represents Taylor Swift today. If you wonder how Freeman swung that, her father was a former Treasury official turned notorious investment banker with a reputation for betraying clients in airline and auto worker unions. Her brother is even worse.

So what would anyone do in this situation? I followed my instincts. I called up the New York Post and The New York Times and tweeted through it. They took my side.

There are few greater pleasures in life than buying a copy of the Post and reading about yourself on Page Six. Well, probably not for her. By the time they ran their story, and the Times called up Freeman’s lawyer, he claimed he no longer represented her in an effort to keep his firm’s name out of the paper of record.

I could never understand people who start a game with every advantage then take their ball and go home because they’re not fixed to win. She was ready to go all the way with all her money and influence then backed off because I stood up for myself and she caught a little flak? What mercy would she have shown me if she won that press cycle?

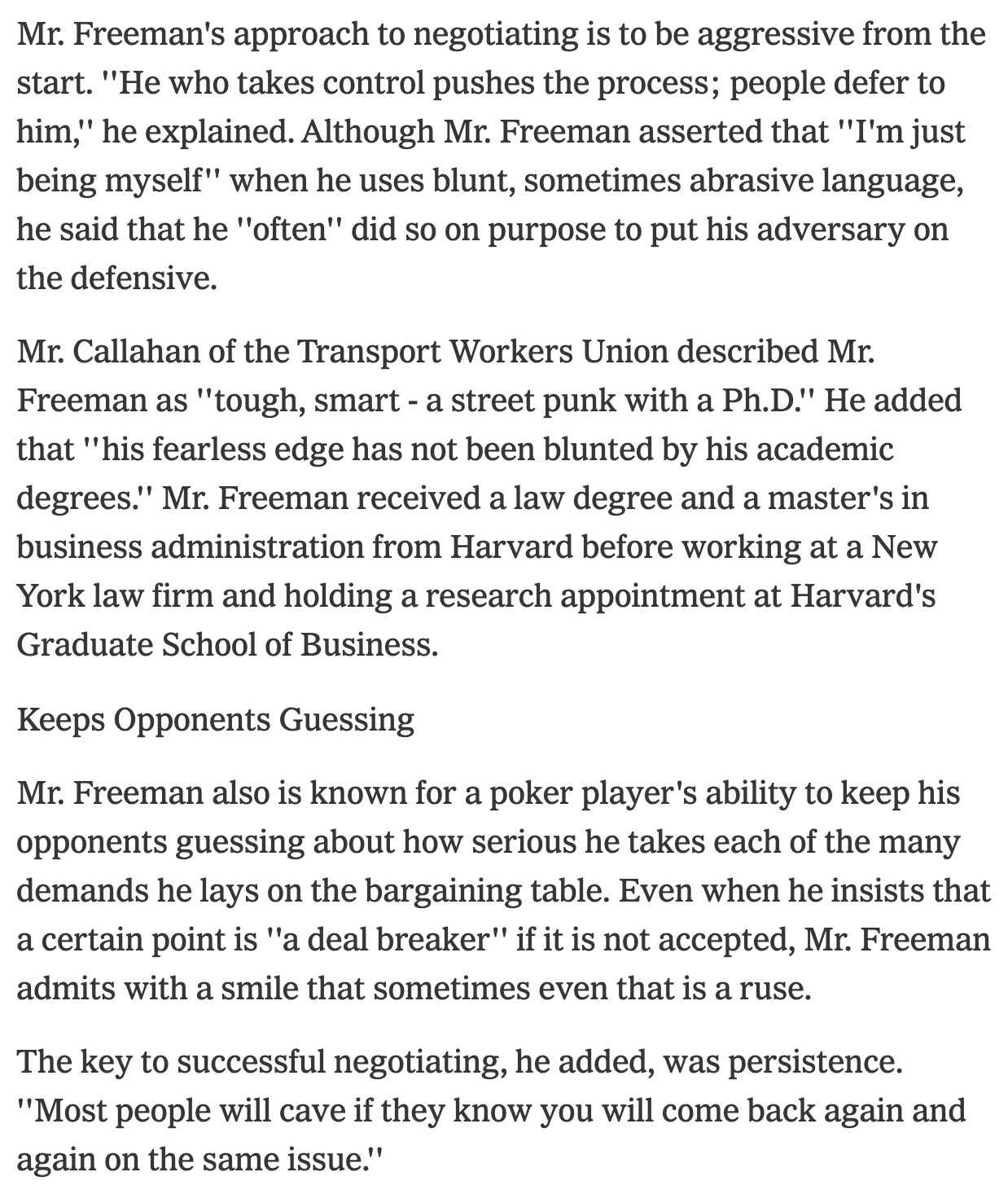

Consider this 1985 profile of her father in The New York Times:

So I bought the domain name for Freeman’s upcoming foodie memoir and began to interview celebrity chefs in her voice. They agreed to be in on the joke. She lost her job and her book was canceled. Time Out even published a mock exit interview with me as the fake Freeman, which led to one of the founders of Eater wanting to fight me backstage at the New York Food & Wine Festival that fall before famous good guy Ken Friedman dragged him away.

All that Twitter hype finally opened some pathways into food journalism. Sadly, the best offer came from Time Out, which offered me the opportunity to write for free. I decided $50 a pop was better than nothing and pivoted. I had my fun but I got in this to be a journalist and pursued local reporting at the Jersey Journal instead.

Whether they regret it or not, the Journal made me the reporter I am today. And while I’m proud of the work I did there, I’m not proud of all the work the paper published.

For example, the editors were openly corrupt and regularly misled their readers. The worst offense, in May 2014, the editorial board endorsed the mayor of my hometown, Mark Smith, even after breaking the story about him allegedly choking out a neighbor two years earlier.

The Journal’s editorial board was so shameless, so unfazed by their own reporting, they cited their own coverage of the incident while endorsing Smith.

Now I wrote for the Jersey Journal from 2010-2013, even after I moved down to Philadelphia for a new job. When I finally returned to the city, all I wanted to do was cover the 2014 Bayonne mayoral race, the most important of my lifetime, but the Jersey Journal was never going to let that happen, so I reached out to another struggling local paper–the Village Voice. Instead of $50, I was offered $500.

I’m not rich and I don’t come from money, but if you give me the green light, I will dedicate my life to an injustice. So I moved back to Bayonne, moved in with my mom, and for the first time in my life I no longer felt like the shy little kid looking up in awe at the grownups. Now I was going through the phone book to chase down rumors, call up kidnappers and hit men, asking them if I could come over. Credit where it’s due, one such man only agreed to speak with me because his daughter was once a Jersey Journal intern.

The Jersey Journal claimed they endorsed Smith because he hadn’t been caught up in any “major incident.” I guess they weren’t looking, because this was my lede:

By March, the porches, and fences of the two-family townhomes that dominated the peninsula city landscape of Bayonne, the gateway to Staten Island on Jersey City's southern tip, had quickly blossomed with signs of spring -- You Can't Put Students First If You Put Teachers Last, Jimmy Davis For Mayor, Re-elect Mark Smith -- but only one banner weathered the last late blasts of February snow: A technicolor tarp of a bubble-blowing Tracy Turnblad battened to the white aluminum balcony hanging over Bayonne City Hall, and advertising the Bayonne High School Drama Society's spring production of Hairspray.

The musical's weekend run opened Friday, March 28th at the bayside school's Alexander X O'Connor Auditorium, where more than 200 proud parents, teachers, friends, and classmates pressed inside a narrow hallway of candy bar concessions and raffle tables, awaiting bouffant-topped ushers to open the doors and dole out Xeroxed playbills 50 pages thick with paid advertisements praising cast and crew, including a trio of sophomores in the musical’s lead roles.

Anselmo "Rocky" Crisonino and his wife congratulated their son on achieving his dream role as Edna Turnblad. Penny Pingleton's father, Bayonne Mayor Mark Smith, opted for politicking over parenting in advance of May's municipal elections; his headshot dominated a page that praised the entire production. (The ad, paid for by his campaign, assured readers in the fine print no taxpayer dollars went toward its purchase.)

Tracy Turnblad's family encouraged their daughter to "Break Legs!" even while her father, Kenneth Baran, an associate of the Genovese Crime Family's LaScala crew, convicted last September in Newark Federal Court for his role in an illegal online gambling operation, remained home on house arrest, a Smith sign outside his front door.

While the three teens showed no signs of drama on stage, cozying around the TV in the Turnblad living room while Link Larkin led the Corny Council through "The Nicest Kids In Town," Crisonino and the mayor held court at opposite ends of the center aisle. Once friends and city hall colleagues, the two men kept their distance for good reason.

With the mayoral election less than two months away, Smith kept a low profile opening night. He sat alone and occupied himself on the phone at intermission rather than work the room. Crisonino, awaiting a June sentencing date in Newark Federal court, felt easy surrounded by family and friends.

A former senior accountant for the city's department of community development, Crisonino was fired from city hall one year prior, and in February of this year he pleaded guilty to charges of bribery, theft of federal funds, filing a false tax return, and–like Baran–partaking in an illegal gambling operation.

That investigation, which spawned the convictions of the mayor's two associates, and the arrests of 12 other LaScala associates by the FBI, was the work of the mayor's opponent in the upcoming race, Bayonne Police Capt. Jimmy Davis.

Next Tuesday, May 13th, Davis is seeking to put an end to an administration that’s achieved the same kind of unchecked power as the criminal organizations he's spent the past 25 years investigating.

"People were afraid," Davis says, of his ultimate decision to run. "They were afraid of Mark and they couldn't find anybody who would be willing to run. I work for the city, my wife works for the city -- are we afraid of retaliation? I'm a big man. I can handle myself."

Everyone knew what was happening in Bayonne, but it was a greater sin to say it out loud. Now the government of my hometown will finally have what it’s always wanted, not one blind eye looking their way but two.

I had first learned about the Bayonne exception back in 2011, while writing about Wikileaks. All the major scandals had been broken by international papers, but there were thousands of documents I thought worth mining for relevant local news. The Journal inexplicably let me run with the angle with one exception. I couldn’t write about an arms dealer operating in my own backyard; I couldn’t write about the only mention of Bayonne in all the Wikileaks cables.

This was what I turned in.

While Jersey City proved a more popular topic in the more than quarter million previously classified documents released by Wikileaks last fall, Bayonne received a solitary mention, one that offered insight into one of the many faceless companies that operate in the Peninsula City's industrial center.

In a July 2009 diplomatic cable sent from Secretary of State Hilary Clinton to the US embassy in Tel Aviv, Clinton asked embassy officials to ensure $72,000 worth of fuse switches, bought by the Israeli Government for use of the country's defense forces, not be repurposed for cluster munitions. Enclosed with her request for an inquiry was a manifest for those switches, listing their seller and shipping agent, Interglobal Forwarding Services, a sixty-five year old, family-operated, freight company located at 8 Hook Road in Bayonne.

Two months later, the embassy responded and confirmed the switches would only be used for their stated purpose.

However, the cable concluded with unanswered questions about why the Bayonne company, in the business of only forwarding other people's cargo, was also listed as the seller, a role traditionally reserved for the components' manufacturer. Asked about this, the managing director and plant manager of Reshef Technologies, the Israeli company taking receipt of the switches on behalf of the Israeli government, would only tell US agents that the sale had been arranged by the Israeli government's Ministry of Defense operating out of New York.While the unorthodox sale of those switches was uncovered through this single mention of Bayonne, additional actions by the Hook Road company featured in a half dozen other cables.

The majority of the cables focused on an April 2008 visit by agents from the US Office of Defense Trade Controls Compliance to the Guatemala City offices of Ori Zoller, an Israeli arms dealer and operator of GIR S.A., Guatemala's largest firearms wholesaler. The agents arrived sought information about two recent incidents involving Zoller and his firm.One incident would later be known as the "Century Arms deal," an illegal sale of mid-century rifles to a Delray, Florida based arms dealer, Century International Arms. The second incident involved a mislabeled shipment of assault rifles, en route from Israeli Military Industries, and destined for the Guatemalan government, but seized in between by US Customs agents in Newark.

Those guns were shipped by Interglobal Forwarding Services of Bayonne.

According to a June 2008 cable, sent from then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to the US embassy in Guatemala, Zoller told agents he believed the application to ship the guns, meant to arm the Guatemalan army's counterterrorism forces, had already been approved. But while clarifying his dealings with the Bayonne company, Zoller shared private misgivings about Interglobal.

Before the agents departed, "Zoller expressed his dissatisfaction with Interglobal as a freight forwarder and claimed GIR S.A.'s reputation as a reliable business had been adversely affected due to Interglobal's lack of "professionalism" and noncompliance with US regulations."

Zoller's reputation was already less than perfect.

When Zoller sought a visa to travel from Guatemala City to Miami Beach one year later, a December 2009 cable read like a laundry list of past misdeeds and suspicions, including the 2007 Century Arms Deal, Zoller’s involvement in the 2003 diversion of Nicaraguan arms to a Columbian group classified as a terrorist organization by the United States, and his 2001 attempt to fulfill a purchase order for a Lebanese arms broker under investigation for suspected ties to Al-Qaeda.

Every Bayonne story created tension and no one liked it when the guy who wrote the annual holiday dining supplement was suddenly going long on arms dealers. But why? I had always believed we were all motivated by the same obligation to our readers.

I could accept the Jersey Journal had no money, no resources, but I always bought into the idea that what we lacked made us scrappy, that our industry was dying so we had to work that much harder to win our readers’ trust and earn their subscriptions. But time and again the Journal failed to hold up their end to both staff and subscribers, so it’s hard today to mourn a newspaper that paid its writers so little money and mind.

The worst part about my editor not publishing the Wikileaks story wasn’t losing out on $50–there were no kill fees–it was how no one at the paper would ever tell me what was so objectionable about the work I turned in.

If someone had told me I screwed up, and told me what I screwed up, I’d be fine with that. I was new and eager to learn. But no one at the paper spoke to me. I was putting days and weeks into stories no one would touch, and icing me out was my editor’s way of telling me I had overstayed my welcome. In three years, I’d never once been invited to our newsroom, never heard my editor’s voice on the phone or seen her face.

As it turned out, there was nothing wrong with my reporting. The Palm Beach Post published a similar story to mine, about Zoller, and sourced from Wikileaks, the week after I turned in my draft. It’s no wonder the Palm Beach Post is still publishing today, and the Jersey Journal is not. You know who else isn’t publishing? The Village Voice.

After signing a contract for my election coverage, the Voice’s editor-in-chief killed my story only after the election already passed. Even when I was being threatened to my face by the mayor’s aides, and anonymously bullied on social media–Twitter karma!–my editor at the Voice wouldn’t once pick up the phone.

When I called up the new editor-in-chief that replaced him, he told me it was worse than I knew. My editor had made his wife, a nutrition influencer, the paper’s dining editor, and they spent months dining out on free meals she never wrote about, before the two of them skipped town for Miami. He traded the Voice for the top job at the Miami New Times.

There’s been plenty written about hedge funds buying up and winding down local newspapers, slashing budgets and selling what’s left of them for scrap. But no hedge fund accelerated the death of the Jersey Journal or Village Voice, they did it themselves.

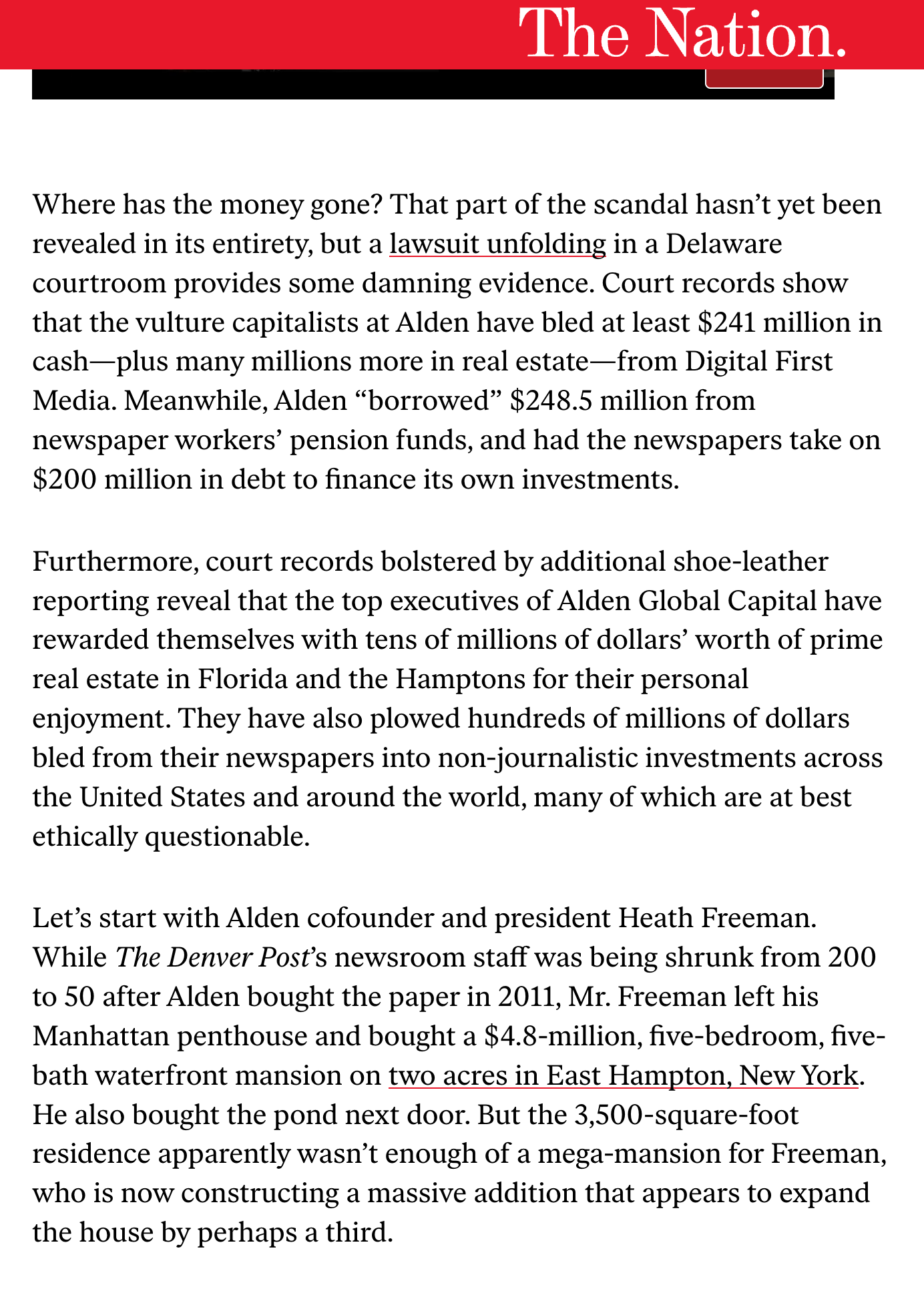

But if the papers had been shuttered by a hedge fund, it might have looked a lot like like Alden Global Capital.

And who’s the managing director of Alden Global Capital?

Via The Nation:

It’s Heath Freeman, Danyelle Freeman’s brother.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider subscribing below for $5 a month, because I am just as unmotivated to write for free now as I was in 2010.